By Ven. Lhundup Samten

There are monks or nuns who find it difficult to depend on other people for monetary support and who, even though they could be helped through sponsorship, decide to work for years in order to be independent. Ven. Samten tells us how one can develop trust and humility by depending on others for one’s subsistence.

Ven. Lhundup Samten (Roger Munro) “Bhikshus there are these four stains because of which the sun and moon do not glow, do not shine, are not radiant. What four? Rain clouds, snow clouds, smoke and dust, an eclipse. In the same way there are these four stains because of which contemplatives and priests do not glow, do not shine, are not radiant. What four? Drinking alcoholic beverage, indulging in sexual intercourse, accepting gold and silver, obtaining requisites through a wrong mode of livelihood.”

This goes back to the Western mind and how we perceive things. Why does everyone have to assert his or her own independence and individualism? Perhaps it is because we cannot trust each other, we cannot allow ourselves to feel vulnerable or too sensitive.

In a way, it is understandable for most Westerners to feel suspicious of others, to lack trust, because so many people have experienced a lack of love in their lives and never learned how to love and trust others. Instead of nurturing feelings of love, suspicion emerges. When these people are asked to give over the responsibility for their livelihood to others, it is a very frightening situation. It is scary to think that someone else is going to have a say or an opinion over what you do. So it does not surprise me that some many of us are resistant, and we want to keep our “own” money and our ‘own’ means of support. This is what we are taught in our society today. But if you really are sincere and want to follow the Dharma path, you cannot be expending all of your time and energy in working for food, shelter, and clothing. There are just not enough hours in the day. This is really a practical consideration; if you are dedicating yourself daily to getting food, clothing, and shelter, there is not much time left over for the practice of Dharma. This is why Buddhist monks and nuns rely on donations from others and monasteries rely on benefactors. It’s because practically, you cannot do both jobs successfully.

This is a problem for all of us. Even if you have your own wealth, you still have to expend a lot of energy managing this wealth, and you stay entangled by many family and social strings concerning this wealth. Of course, if you have independent money, you can do a lot of good by practicing generosity. But again, doing your own practice becomes difficult. You always have to make sure your money is properly invested and is increasing. You become a self-employed businessperson looking after your financial affairs.

For all of these reasons, I think it is most beneficial for those who wish to practice seriously to have benefactors to help minimize the amount of time and energy spent on worrying about financial matters. I think it is just a very practical matter that if you are going to practice seriously, you need benefactors to help you practice. People who themselves cannot practice seriously can help you, and you can then dedicate your practice to their welfare. In this way everyone benefits. You have the hours in the day to get your practice done, and your benefactors receive merit from helping you. They create the cause to have the same thing happen to themselves – to be practitioners helped by other benefactors, whether later in this life or in a future life.

When I met Geshe Yeshe Tobden at Land of Medicine Buddha, I was introduced as this ‘great meditator,’ having just finished a ‘big deal retreat.’ Immediately, one could see that he was not happy. Geshe-la ate his dumplings and then hurried away without saying one word to me. Fortunately, the next day I had the good karma to give him a ride to San Francisco. For the first part of the trip, not one word was spoken in the car; everyone just seemed to be engaged in his or her own serious practice. Half way into the trip, though, Geshe-la turned to Paula (Munro, now Ven. Lhundup Ningje) and, through his translator, asked, “How did you people get your food while on retreat?” Paula started to explain to him the logistics of how food was delivered to us. Geshe-la interrupted and asked: ” Where did the money come from to provide this food?” She told him that we begged. We solicited benefactors amongst our friends, and many people got involved to support us during our retreat.

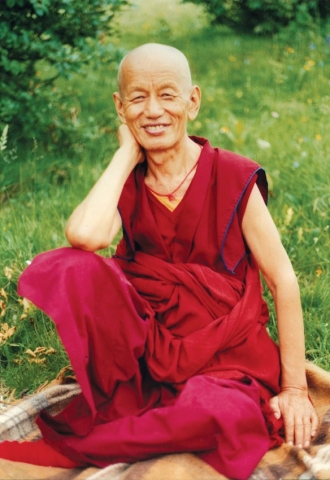

Geshe Yeshe Tobden

This news made Geshe-la very happy, and he reacted with great animation, putting his arms around me, shaking me up by the shoulders and inviting me to stay with him whenever I came to India. It was a very touching experience. Geshe-la continued to explain that he had traveled all over the West and had seen every part of the Dharma being practiced here, but the one thing he found lacking was this aspect of practitioners and monks and nuns relying on benefactors and not having to look after their own wealth.

Geshe-la encouraged us to keep up this aspect of the practice because he said that it is the most important part for people to see. That is, to see that the Buddha’s promise is true: that if you give up this life and practice seriously, although you won’t become a millionaire, your basic necessities will be provided. That is the most basic practice for us to do as monks and nuns and as meditators: to allow ourselves the lack of control that it takes to be associated with others in that way. To let go of our desire to control things and take care of ourselves out of fear and lack of trust in others. This will bring us a long way toward coming that much closer to attaining inner peace and to increasing our love and trust for other precious sentient beings.

It is difficult to let go of this level of control over our lives, but it is a part of the lesson we must learn. We all want to control our lives, to come and go as we please, to do what we want. But, when we have to rely on the kindness of others, things don’t always work out exact as we have planned. We cannot always do exactly what we want; we often have to compromise and give up some of our freedom. But actually, we gain much more than we give up. We gain the time and liberty for our practice and freedom of the mind.

Over time, we will gradually realize that the only way really to be able to practice is through giving up other things. When we give ourselves over to the Dharma, things that have preoccupied us in the past, such as financial support, will be taken care of. This is true now and has been true for over 2,500 years. However, in the West we still have to begin to realize this.

We must accept that Buddha’s promise – that anyone wearing the robes of a monk will never go without food or shelter – is true and not cling to our wealth. In accepting this, we must also be willing to accept a certain level of poverty. If you are already poor, this may not be a problem, but if you are used to having your own wealth and support system, this “giving up” is going to be difficult at first. I feel that you have to reach a certain point of poverty before the Buddha’s promise is activated. You must have a need before others can fill it for you. If you don’t have a need, no one can fill it.

This is something that will have to take root in Western consciousness as we begin to understand that practicing Buddhism is a full-time job. If you really want to learn the Dharma, you must become a full-time Dharma professional. You cannot mix this practice with other kinds of livelihoods. Actually you can, but then you are not endeavoring to be a professional Dharma practitioner. If you are a backyard mechanic, you don’t have a huge workshop with a vast assortment of tools; you are limited to a small workspace and are, therefore, limited in what you can do there. For that matter, how many successful part-time doctors or part-time lawyers are there? Even in the professional world, to achieve the most out of your vocation, you must apply all your energies in that direction. It is the same with your Dharma practice. I am not saying that we all must leave our households to become monks and nuns. What I am saying is that we all must realize how a sincere practice in the Tibetan tradition is a serious undertaking that requires much time and effort. In order to maximize those things, some of us will decide to become professional Dharma practitioners and give up whatever we must to achieve this goal.

Another thing that is sometimes misleading is the concept that we all have to enduring great hardships and deprivations – to practice like Milarepa, Tilopa, and Naropa. That is not the way for most of us. We all need to have a minimal standard of living to survive. In 1996, I was with Kirti Tsenshab Rinpoche in New York City, at the end of our retreat. We were joking with Rinpoche, apologizing for not attaining enlightenment during the retreat, and Rinpoche told us not to worry, that for most of us it takes a very long time and very good conditions to gain any realization and to make the practices work. Rinpoche reminded us that these good conditions include a place in which we can flourish, with good food and shelter, and that we need to keep healthy and warm. We don’t have to suffer like Milarepa – that would be going to an extreme. Instead, we require a middle ground: sufficient support to keep us going, but without too much abundance or indulgence that will hold us back. Once on this middle ground, sincere practitioners can accomplish much and experience many realizations.